Fish and Fishing in the Rivers and Streams

in the Salmon River, NY Area

Introduction to The Salmon River Area

The Salmon River area, located in the Tug Hill region of New York, is widely known for it fantastic chinook (king) salmon runs each fall, and is becoming better known for its excellent steelhead and brown trout fisheries. The Salmon River is the principal

angling stream in the region. Its holds this distinction for several reasons: It is relatively large, it has a relatively constant flow due to water releases from upstream dams, and it is heavily stocked with Chinook salmon which are raised in

the hatchery on the river.

River and stream fishing in this region is principally for chinook and coho salmon, steelhead and brown trout. Atlantic salmon and smallmouth and largemouth bass can also be found in these waters. Chinook salmon in the region generally average 15

to 25 pounds. Steelhead average from 5 to 15 pounds, and brown trout average from 10 to 15 pounds. By anyone's standards, these are large fish, and they are all aggressive fighters and a challenge to land.

The Salmon River received its name not for the chinook salmon that now make their fall runs there, but for its once-famous runs of Atlantic salmon. In the past Lake Ontario was known for the largest population of lake dwelling Atlantic salmon anywhere.

By 1900, Atlantic salmon were gone from Lake Ontario and its tributaries, including the Salmon River. The last recorded Atlantic salmon at Pulaski was found in 1872. It is generally believed the extirpation of Atlantic salmon was the result of

a number of factors, including over-fishing, pollution, introduction of exotic species into the lake (especially the lamprey eel), and destruction or degradation of their spawning habitat.

Millions of chinook were stocked into Lake Ontario in the late 1800s, but they did not survive. In the early 1900s rainbow trout were stocked into the Salmon River. Some of these fish survived and some ran to the lake each year. Others were stocked

above the reservoirs and have also survived. However, the sport fishery on the Salmon River was insignificant from the late 1800s until the 1960s.

In the 1960s New York State began a program to revitalize the sport fishing in the Lake Ontario watershed. Beginning in 1968 the state began stocking coho salmon in the Salmon River and other Lake Ontario tributaries, and chinook were first stocked

regularly in 1969. In 1973 New York State began stocking steelhead and brown trout into Lake Ontario and its tributaries. In 1974 lake trout, a species native to Lake Ontario, were also being stocked into the lake. Now the state stocks approximately

1.6 million chinook, 250,000 coho, 50,000 landlocked Atlantic salmon and 800,000 Steelhead into the Lake Ontario tributaries.

Salmon and trout fishing opportunities currently exist on approximately 12 miles of the Salmon River from its mouth to the dam at the Lighthouse Hill Reservoir. The reservoir behind this dam is known as lower reservoir. Construction of the dam stopped

all salmonoid migrations at the dam, and there have never been attempts to permit any spawning fish to pass this obstruction.

The regional power company, Orion Power (formerly Niagara Mohawk), operates the hydroelectric power generation station at the dam. There are two dams and two reservoirs on the river. The lower reservoir is the Lighthouse Hill Reservoir and the upper

reservoir is the Salmon River Reservoir. The spectacular Salmon River Falls is located between the two reservoirs.

In 1981 the Salmon River Fish Hatchery began operation. It is located just above the lower fly fishing only section of the Salmon River on Beaverdam Brook. It raises approximately 250,000 Coho, 3.2 million Chinook, 750,000 Steelhead, 300,000 Brown

Trout and 150,000 Landlocked Salmon each year.

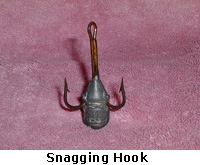

For years snagging was permitted on portions of the river. There were strong critics of this practice. Anyone who has seen how it is done - with very large weighted treble hooks flung across the river and violently jerked back - could understand why

concerns about this practice would be voiced. Ultimately, in 1993 the DEC banned all snagging on the river.

The flow of the Salmon River is controlled by the power company (formerly Niagara Mohawk). The more water it decides to release, the greater the flow. Generally it will release more water after heavy rains or an ice melt-off, but this is not always

so. You can call their hotline for information on the flow, which is given at the top of the Reports page of this site. A flow of "one gate", or 750 cubic feet per second (cfs), will produce a moderately fast flow. A half gate is often

considered ideal. Two gates will be a hard flow and will be impossible to wade across in most areas.

In the mid-1990s the power plants were due for relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. As part of this process, numerous interested groups participated and as a result, the power company now must maintain minimum flows for the river

throughout the year (except in emergencies). Beginning in 1997, there must be a minimum flow of 185 cfs between May 1 and August 30, 335 cfs between September 1 and December 31, and 285 cfs between January 1 and April 30. There must also be five

"whitewater" releases during the year (of either 400 or 700 cfs), one in June, two in July, one in early August and one during the Labor Day weekend. The whitewater releases are to provide recreational activities on the river, such as

kayaking. The last whitewater release may also produce a first run of chinook.

It is hoped these minimum flow requirements will return the river to more natural and consistent water levels, which, in turn, will improve the natural reproduction of aquatic and insect life and natural fish reproduction. It is also hoped the minimum

flows will produce a resident brown trout population. These minimum flows have already produced a significant increase in the insect activity on the Salmon River. Before the minimum flow requirements, the only significant hatch on the river was

the caddisfly. Now the river is beginning to have all the traditional insect hatches, which is certainly a positive sign for the health of the river system.

In the early 1990s concerns began to surface about declining numbers of chinook salmon being harvested, especially in Lake Ontario. Stocks of alewives, which are the primary forage food for chinook and other salmoniods in the lake, were dropping.

Ultimately New York State and the Province of Ontario decided to reduce the numbers of salmoniods stocked, especially chinook which are the largest and fasting growing of the stocked predator fish. The levels of chinook stocked were reduced by

over 60%, and the level of lake trout stocked were reduced by 50%. Stockings of steelhead were increased slightly. After complaints of decreased populations of chinook, stockings were increased in the mid-1990s, but to a level below the high stocking

rates prior to 1992. The responsible agencies continue to struggle with the difficult task of trying to find a suitable balance to maintain a sustainable fishery in the ever-changing environment of Lake Ontario and its tributaries.

New York State has acquired public fishing easements on most of the length of the Salmon River outside the Douglaston Salmon Run area. These public rights make angler access to the river easy and convenient.

Currently the New York State Department of Health has issued an advisory which recommends that persons eat no more than one meal per month of smallmouth bass taken

from the Salmon River. Oddly, although the state recommend against eating any Chinook from Lake Ontario, it does not currently have an advisory in place against eating Chinook taken from the Salmon River or other streams in the region.

Currently the Salmon River below the dams provides fishing for chinook salmon, coho salmon, brown trout, Atlantic (landlocked) salmon and two strains of steelhead from its mouth to the Salmon River Reservoir. Each of these game fish is described below.

There is also fishing above the dams for native rainbow and brook trout.

Fish of the Salmon River Area

Chinook Salmon

The Chinook or King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) of the region are derived from the chinook of the Pacific Coast of North America. They spawn in the fall, generally between October and November. The female creates a "redd" in the gravel

by pushing away the stream gravel with her tail. Once the nest is built, one or more male salmon fertilizes the eggs. The female then buries the eggs by pushing gravel loose just upstream of the redd. These salmon die after spawning.

In the late 1960s the New York DEC began to aggressively stock chinook in Lake Ontario. The eggs hatch in November and December and the fish are placed into the rivers as three inch fingerlings in May or June to be "imprinted" with the scent

of the stream. This imprinting allows them to return to the stream in which they were released. Typically a fully-mature Chinook which has returned to spawn is either two or three years of age and will weigh between 15 and 25 pounds. Sometimes

juvenile Salmon, known as "jacks", will make "false" spawning runs and be found in the river along with mature fish. Occasionally four year old chinook will be found in the rivers. The current Great Lakes record Chinook Salmon

was taken from the Salmon River in 1991 and weighed in at 47 pounds and 13 ounces.

Male salmon and steelhead can generally be identified by their hooked lower jaw. The closer they get to spawning, the more pronounced the hook in their jaw. Typically females have a blunt or rounded nose which does not deform during spawning.

Chinook are bright silver while in Lake Ontario and as they enter the river, and become darker the longer they are in the river. A chinook can be differentiated from other salmon and steelhead by its black mouth and black gums. It also has spots all

over its tail.

Recent studies indicate there is considerable natural reproduction of chinook salmon occurring in the Lake Ontario tributaries in general. Many native chinook have recently been found in seines of the Salmon River. Research is continuing to attempt

to assess the levels of natural reproduction in these waters.

Coho Salmon

Coho or Silver Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) are smaller cousins of the chinook and adults average 7 to 10 pounds. They were first stocked regularly into Lake Ontario in the late 1960s along with the King Salmon. Cohos are stocked in the Spring at

about 18 months of age, after spending more than a year in the outdoor raceways of the hatchery. They are about 5 to 6 inches long when released. Most returning coho are two years of age. Coho spawn slightly later than the chinooks, and they too

die after spawning.

The coho salmon can be identified by its black mouth but white gums. It also has spots only on the upper half of its tail.

The current Great Lakes record coho salmon was also taken from Lake Ontario off Oswego in 1998 and weighed in at 33 pounds and 7 ounces.

Atlantic Salmon

Atlantic or landlocked salmon were once native to Lake Ontario and the Salmon River. Since 1996 there have been serious efforts to reintroduce this species into the Salmon River. However, they seem to be more susceptible to adverse conditions and

their survival rate has been lower than the other salmoniods stocked in these waters.

Atlantic salmon run the rivers from June through November. They spawn in the fall, generally later than chinook salmon. Since they are summer runs, they provide an opportunity, along with the Skamania steelhead and native brown trout populations,

for a summer fishery in the Salmon River. Like steelhead, Atlantics often survive the spawn to return another year.

Adult Atlantics average from 12 to 30 inches in length. The state record was taken from Lake Ontario in 1997 and weighed 24 pounds and 15 ounces.

Atlantics can be easily confused with brown trout. Both brown trout and Atlantic salmon have white mouths and gums. The maxillary or jaw area of the Atlantic salmon typically extends on the edge of the eye, while the maxillary of the brown trout typically

extends significantly past the rear edge of the eye. Another distinguishing feature is at the caudal peduncle, which is the area of the fish just ahead of the tail. On an Atlantic, this area is narrow and tapered, while on a brown trout it is

thick and stocky. As a result, an Atlantic salmon can often be "tailed" (i.e., held by grabbing the fish just ahead of the tail), and a brown trout cannot. The tail of the Atlantic is also slightly more forked; the tail of the brown

trout is square.

Steelhead

New York State stocks two strains of steelhead in the region. Both strains are derived from stock taken from the Pacific Northwest. They are commonly referred to as "lake run rainbow trout" and are anadromous, which means they migrate into

streams to spawn. Steelhead can survive the spawn and may return to the river multiple years to spawn.

The strain which is stocked in greatest numbers and which has been stocked the longest is known as the Chambers Creek winter run strain. They begin entering the streams in mid to late October. They often hold in the rivers until April and sometimes

into May. Often warm weather and high water flow triggers another run. Most winter run steelhead are ages three, four or five. These fish average 7 to 12 pounds in the rivers and streams. The state record steelhead (recorded as a rainbow trout)

was taken in 1985 and weighed in at 26 pounds and 15 ounces.

Winter run steelhead spawn from mid-March through April.

Skamania steelhead are newer to the region, and are "summer run" steelhead. Although they too spawn in the spring, they are bred to run in the river during the spring and summer months. This program is relatively new and its success is still

being evaluated. It is hoped that with the stocking of Skamania steelhead, and the more consistent river levels during the summer mandated by the recent relicensing, there could be a viable fishery for steelhead during the summer, together with

Atlantic salmon and native brown trout. Skamania steelhead first return at age three, and four year olds dominate the runs.

Unlike the salmon, both strains of steelhead often survive after spawning and return to the Lake.

Steelhead often have a reddish streak along their midline. They have a white mouth and white gums. The longer they have been in the river, the darker they tend to become.

Brown Trout

Brown Trout are not generally anadromous and therefore do not regularly run the rivers like the salmon and steelhead. Nonetheless, some brown trout from Lake Ontario make their way into the river and are taken, usually later in the fall along with

steelhead. The DEC is also attempting to develop a population of resident brown trout, to provide a summer fishery. It is hoped these resident brown trout would be in the 15 to 18 inch range during the summer months.

Lake run browns, which lived in the lake and made their way into the river, can be large and in the Salmon River they average 7 to 8 pounds. They spawn in the fall. There is also typically a run of brown trout in the Salmon River in late June or early

July.

Etiquette

Proper etiquitte is essential for maintianing good landowner relations, improves the image and reputation of anglers, and makes the experience more enjoyable for everyone involved. We suggest the following points to consider when fishing:

- Upon arriving be sure you have parked in an approved area (see river and stream descriptions) and make sure your vehicle is off the road. Do not park on anyone's lawn and do not block any roads or driveways.

- Most of the streams and rivers are on private property. If you are fishing on private property, ask permission to fish if you can identify the landowner. Consider offering the landowner a fillet or to clean up the area in return for the privilege

of fishing on his or her property.

- If the water you are fishing is near houses or a residential area, remain quiet, especially at dawn.

- Walk in or along stream beds as much as possible; avoid private lawns as much as possible. Keep flashlights pointed at the ground.

- Never "relieve yourself" within sight of any person or home. Nothing will make the landowner mad faster.

- Be courteous to those already on the water. Walk behind other anglers and out of the water if possible. If you must stay in the water, walk with a minimum surface disturbance. Do not walk through the area where others are fishing. If the area

is deep, you should probably be fishing it, not walking through it.

- When conditions are crowded be aware of your fellow anglers. Watch where you cast to avoid tangles and injury. Remember tangled lines happen even to the best anglers; just be patient and offer to untangle the lines.

- If you have the good fortune to have a prime fishing spot and are therefore able to hook up multiple fish, consider rotating out of that spot. You may find it far more gratifying to let a frustrated angler have the spot and watch him or her catch

a fish than for you to catch your twelfth fish while others are catching none.

- Just because you were "there first" does not mean you can continue to fish as large an area as you please regardless of how many other anglers arrive. Fish an area appropriate for the number of people fishing around you.

- In crowded conditions, play your catch only as much as necessary.

- If your are inexperienced, the best education is from watching those who are successful. Crowded stream conditions seem to form a cooperative camaraderie among anglers that can be enjoyed even when it is "elbow to elbow." Many anglers

are more than willing to assist you if you ask.

- Foul language is unnecessary, especially around younger anglers.

- Be tolerant of the inexperienced angler . . . remember we were all beginners once.

- If in a crowd, alert others when you have a "fish on." If another angler is fighting a fish, bring in your line and, if necessary, move out of their way to let them land the fish, just as you want the same consideration if you were fighting

the fish.

- Leave with everything you bring. Litter can be a real threat to our fishing privileges. Good anglers will demonstrate their respect for the fishery and the river by picking up even what they did not leave behind.

- Do not keep any more fish than you are realistically going to use. If you do not think you will eat the fish, put it back gently and give someone else the opportunity to enjoy the catch. These fish are not an inexhaustible resource.

- Do not clean fish in or around the streams. It is discourteous to residents and other anglers, and it is prohibited by the Fish Commission.

Fishing Seasons

Summer Fishing

During the summer, anglers may find Atlantic salmon, resident brown trout and Skamania steelhead. With the recent minimum river flow requirements, and the increased emphasis on stocking these species, the opportunities for summer angling are improving

considerably.

Anglers may also fish for smallmouth bass in the river during the summer, and for northern pike in the estuary. Both can be very good fisheries.

Fall Fishing

Chinook salmon are king in the fall. Each year these monsters enter the rivers in early September to spawn. When the runs will start, and how long they last, varies year to year. Typically by mid-October the main runs are over and many dead salmon

will litter the sides of the river. The coho runs generally coincide with the runs of chinook, and coho and chinook are often interspersed in the same parts of the river.

Often the runs will follow significant rain events or major releases of water on the Salmon River. After the water rises and as it begins to drop, the salmon will make a run. These runs of fish will then make their way up the river. Thus, one day

these could be large numbers of fish in Douglaston Salmon Run area, the next day they are past Pulaski headed for Altmar. Because the flow of the Salmon River is controlled by the outflow from the upstream dams, a large release of water by the

power company can simulate a rain event and also cause a run of salmon.

By October the Steelhead will also begin to enter the rivers and streams to feed on the salmon eggs from the spawning salmon. Brown trout enter the rivers and streams between mid-October and the end of November.

Winter Fishing

During winter the fishing is mostly for steelhead. The Salmon River remains open most of the winter because of the constant discharge from the bottom of the reservoirs upstream. During the dead of winter the fishing pressure can be very light.

Streams other than the Salmon River may freeze during the winter and become unfishable. During the coldest periods, fishing the Salmon River can also be difficult as ice and slush form, especially further downstream from the dams.

Spring Fishing

Spring fishing is also primarily for winter run steelhead. In late spring, anglers may also find Atlantic salmon in the rivers. Steelhead fishing can be very good in March and into April. Once the water warms, the steelhead make their way back to

the lake to feed during the summer. Generally the winter run steelhead fishing ends by mid-May.

Drift Boat Fishing

The Salmon River can be fished with a drift boat. These are sturdy aluminum watercraft (known as McKenzie River drift boats) with a turned-up bow, oars and a heavy anchor. Drifting is a great method for covering a lot of area, and reaching the middle

of pools that are difficult to reach by wading. Even if you do not fish, they are a relaxing and enjoyable way to explore the river valley.

Many local guides fish from drift boats. They permit anglers to fish by casting from the boat, by back bouncing (often with plugs), or they pull out and permit anglers to wade fish in target areas.

Tackle and Gear

Fishing for chinook, cohos, steelhead and brown trout are generally done with either a spinning or fly outfit.

Although during the fall it may be possible to be fishing over chinook salmon, cohos, steelhead and brown trout at the same time, generally the gear for chinook is different that than the gear for all other fish because the chinook are so large.

The different gears are described below.

Regardless of the type of rod and reel used, there are other gear requirements. A good pair of waders is essential. Chest waders give greater versatility and allow you to reach deeper areas

that might exceed the height of hip boots. In times of low flow, or on the smaller stream, hip boots may be adequate. In the colder months, insulated waders are essential. Many anglers opt for neoprene chest waders. In times of high water, consider

wearing a life preserver or an inflatable vest.

Many anglers use boots with spikes for traction. Many anglers use cleats such as "corkers" on the Salmon River, and they are required in the Douglaston Salmon Run after November

1. In the early season, the stream bottoms can still be algae covered and very slippery. If you do not wear cleats, felt-bottom boots provide better traction than rubber-bottomed boots. However, once it snows, the snow sticks to felt-bottom boots

and they can become difficult. If you are not sure of foot, wear spikes and use a wading staff.

Some anglers carry a net on the streams and others do not. Whether to carry one depends to a large extent on how concerned you are about landing a fish. If you plan to release the fish, then there is less need for a net (especially since the net can

injure the fish). If you use a net, use a large one - a standard trout net will not land the fish in these rivers and streams. Many anglers release all the salmon or steelhead they catch, and often they carry no net. Even chinook can be "beached"

or "tailed" in many places, and therefore taken without a net. If you want to be sure you land the fish you hooked, and don't mind carrying a net with you along the stream, a net is a good idea.

Like with any stream fishing, a good fishing vest is a must. In the winter, gloves are also necessary. When the water is

not too high or cloudy, most fish in the river can be "hunted" or spotted in places in the streams. A pair of polarized sunglasses is another necessity for spotting fish in the streams.

If you plan to keep any fish, a good stringer is necessary. A traditional stringer will not hold a large chinook salmon - use either a heavy-duty stringer or just rope.

Spinning Gear

Hook, Line and Sinker

Although spinning gear still seems to predominate on the streams, fly fishing equipment steadily grows in popularity. Spinning gear for chinook is larger than almost any inland stream fishing in the eastern United States. Typically anglers use line

anywhere from 12 pound test to 20 pound test, although 14 pound is generally adequate. These heavier lines are relatively easy to follow, so use line with the lowest visibility possible. Alternatively, try using a fluorocarbon leader of at least

3 feet tied to the end of the monofilament. The fluorocarbon presents an almost invisible line to the fish. If you do not like making line-to-line connections (using the likes of the barrel knot), you can use a small two-way barrel swivel and

connect the monofilament to one end and the fluorocarbon leader to the other.

Previously, the state required the use of a "terminal rig", with a swivel or other break in the line above the hook. This is no longer required (except in the DSR), but it still often used in this area. A swivel several feet from the hook

provides an easy method for connecting a tippet and a dropper for weight. Still others use pencil lead.

Since almost all salmon and steelhead are taken near the bottom, it is necessary to get your offering down. This generally requires split shot. The amount and size of the shot depends to a large extent on the flow. Carrying split shot from size BB

to size 7/0 should cover all conditions. The Salmon River can have a very strong flow and heavier shot may be necessary. However, many anglers put far more weight on that is necessary, and this results in large amounts of lost line and weight

strewn about the river.

Some anglers also use "slinkies", which are pieces of parachute cord with lead pellets inside. Typically these are attached to the line with a snap swivel, with the snap being placed through the slinkie. This rig is designed to reduce the

frequency of having the weight hang-up on the river bottom. Other anglers use pencil lead. Some anglers use weight on a "dropper", which is a short piece of usually lighter-test line on which the weight is attached. With a dropper, if

the weight gets caught on the bottom you can pull of the weight or break off the dropper without losing the rest of your rig.

There appears to be no consensus of the type of hook to use for chinook. Some use standard hooks, others use the traditional salmon or steelhead hook, which is a thicker, short shank, eye-up hook. Hooks used are larger than normal, with hook sizes

of at least size 2 or larger commonplace.

Gear for steelhead is lighter and more delicate. As the chinooks leave the rivers, the gear gets lighter. For steelhead and browns, line of 6 or 8 pound test is used, with 4 pound line being used in very clear or low conditions. If you do not use

a float or strike indicator, use line with some visibility so it can be watched. Again, you can use a fluorocarbon leader to reduce the visibility of the line presented to the fish.

The hooks used for steelhead and browns are also smaller and lighter. No particular type of hook is needed. However, the traditional salmon or steelhead hook, which is a strong, short shank, eye-up hook, is often used. The hook size depends on the

river conditions and the type of bait used. A size 4 should be big enough under any circumstances. A size 10 or 12 will get more strikes in clear conditions, but landing a fish with this size hook can be challenging. Experienced anglers, who don't

mind trading more hook-ups for fewer landed fish, will fish with hooks in size 14 or smaller.

Rod

The common rod for spin fishing for chinook is a long (7 to 8 foot) or an extra-long (9 or 10 foot) rod designed to land a big fish. Typical rods are designed for lines of 12 to 20 pound tests. If the rod is too light, you will never land a chinook.

Again the rods for steelheads and browns are lighter. By winter, anglers tend to use rods specifically designed for drift fishing for steelhead, which are extra-long rods designed for four to eight pound line. The "noodle rod", which is

very long (often 10 feet or more), and extremely soft for fishing very light line (e.g., 2 pound test), is becoming less popular. Most steelhead fishing in the streams is drift fishing. For drift fishing, many prefer a short butt-end to the rod.

A longer rod allows you to keep more of the line off the water to get a better drift, and the short butt is easier to handle. Steelhead can take a hook very lightly, so a sensitive rod is helpful. On the other hand, they can be aggressive fighters,

and a rod with some backbone is also helpful.

Using a spinning reel on a fly rod is not uncommon. The fly rod is sensitive, long, and has a short butt.

Reel

When fishing for chinook, a large capacity spinning reel with a good drag is essential. When a 30 pound chinook heads for Lake Ontario, you will be thankful for all the line you have on your spool. A front-drag reel with capacity to hold at least

120 yards of 15 pound line should be adequate.

No particular size of reel is essential for steelhead. As long as the spool has the capacity for enough line to play the fish and a drag strong and smooth enough to withstand the stress, the reel should work. Chinook sized reels are not necessary

for steelhead. Medium-sized reels with a smooth drag, with capacity to hold at least 120 yards of 8 pound line should be adequate. You will be really pushing your luck using ultra light gear.

Fly Gear

Line and Leader

Floating line is the norm. The streams are typically too shallow for any type of sinking line. For chinook, a WF10F or a DT10F line should work. Be sure to use sufficient backing to be able to play the fish. If you use a lot of weight on a fly line

for chinook, a running line can be used rather than a tapered line. Use line of .029 or .032 diameter. Some anglers now use a sinking tip tied to a floating line to get the fly down to the fish.

For other river fishing such as steelhead and brown trout, again floating lines are used. However, lines are generally 7 or 8 weight.

Leader and tippet sizes depend, as always, to a large degree on what flies you are using. Many anglers tie their own leaders. Since you are often fishing with split shot, this is not finesse fly fishing and it is not necessary to have a perfectly

tapered leader. Similarly, the leader need not be too long for this type of fishing, unless you are fishing in very clear water with a very small fly. Under normal conditions, a leader and tippet combination that is not longer than the rod itself

should work. A longer leader and tippet combination on the smaller streams will be too long and difficult to handle. Many anglers tie in at least one length of high visibility line (such as "Amnesia") in the upper end of the leader.

Use of a fluorocarbon tippet is becoming more popular because of its nearly invisible properties.

Not surprisingly, small flies (e.g., size 12 or smaller) should be fished with a light tippet. 5x and lighter tippet will have difficulty landing steelhead. 3x and 4x tippet is popular for steelhead. Fishing a power egg on a size 6 hook with several

split shot in high water can be fished with straight monofilament as a leader and tippet. When fishing for chinook, tippet material of from 8 to 12 pound test is common.

Rod

For chinook, anglers typically use 9 or 10 foot rods from 7 to 11 weight, with 9 and 10 weights probably the most common. Most rods in this class have a fighting butt, which is helpful. For steelhead and brown trout anglers typically use rods from

6 to 8 weight. A 6 weight rod will not give you much backbone to land a large steelhead, and an 9 weight rod has more than enough backbone.

Reel

Any respectable fly reel will work, but a reel without a disk drag will make landing a chinook very difficult. A smooth disk drag is certainly helpful for playing a larger fish. For chinook, a reel which accommodates a 9 to 10 weight line will work

well. If you can afford it, try an anti-reverse reel for chinook. For steelhead, a disk-drag reel which accommodates a 7 to 9 weight line is adequate. Be sure to use plenty of backing; these fish can make very long runs. A reel for chinook should

hold at least 150 yards of 20 pound backing. High-visibility backing is a good idea so you and other anglers around you can see where your line is.

Bait and Flies

Common baits used for spin fishing for chinook salmon include the following:

- Egg sacks (of either salmon or steelhead eggs)

- Skein (of either salmon or steelhead eggs)

- Night crawlers (usually not used during the winter)

- Artificial salmon eggs (like Crazy Eggs and Jensen Eggs)

- Power Bait

- Sponge (many do not consider this a "bait" but as merely a way to satisfy the requirement that there be something on the hook)

Common baits used for spin fishing for steelhead include the following:

- Live or salted minnows

- Power bait or power nuggets

- Egg sacks (of either salmon or steelhead eggs)

- Skein (of either salmon or steelhead eggs)

- Night crawlers (usually not used during the winter)

- Single salmon eggs (the variety in the small jars in oil, or the loose eggs found at the bait shops)

- Grubs (a.k.a. maggots)

Lures are not too commonly used in the streams. However, J-plugs are fairly commonly used for chinook by either spin fishermen or when back trolling from a drift boat. These lures can also be abused as a means to snag salmon.

Fly patterns for salmon tend to be flashier than other flies. The most common flies for salmon are the Estaz Fly, Comet, Woolly Buggers, Egg Sucking Leaches and Glo-Bugs (imitates a salmon egg; tied with Glo-Bug yarn). Typical fly sizes range from

size 2 to size 8.

The two most common flies for steelhead are the Glo-Bug (imitates a salmon egg; tied with Glo-Bug yarn) and the sucker spawn (imitates sucker eggs). Sizes 10, 12 and 14 are the most popular.

The local bait shops will carry the popular baits and lures. For fly patterns, check the Flies and Lures page on this site.

Fishing Techniques for Salmon and Trout

Salmon and steelhead fishing in these rivers and streams is heavily dependent on the water flow. During or just after a good run, the fish may be about anywhere - in the pools, in the riffles, in deep water and in shallow. If there has been no recent

run, the fish will tend to be in the pools or deeper water (unless they are spawning, in which case they may be in the riffles). When the water is very low and clear, typically the fish will be only in the deeper pools.

Most fishing for salmon and steelhead is drift fishing (sometime called "dead drift" fishing). The common method is to cast across and up the stream, and let the line drift naturally down stream. Both salmon and steelhead are almost always

near the bottom (if they are suspended near the surface, they are much more difficult to catch). If the hook is fished near the surface, you have little chance of getting a strike. You need to get the fly or bait down where the fish are holding.

If you never feel the bottom, you are probably not down far enough. If you keep getting hung-up, reduce the weight on the line.

A typical spinning rig without a float includes a single hook tied directly to the line, with several split shot about at least 12 inches above the hook. Use enough weight to get the line down so you can occasionally feel the bottom, but not so much

weight that you keep getting hung-up on the stream bottom. Again, many anglers still use a swivel about two to three feet up the line, with a lighter leader and the weight either on the line above the swivel or on a dropper off the swivel.

Another common rig is to use a small float on the line above the hook. This works well in the deeper pools, and avoids losing so much tackle on the stream bottom. Use the smallest float and least weight you can get away with. Try to keep a minimal

amount of slack in the line. Also try to mend the line to keep the float as close as possible to the hook below it. Since the water on the surface moves faster than the water below, the float will tend to get ahead of the hook and "pull"

the hook along behind it. If the float gets ahead of the hook below, the presentation is less natural and less likely to provoke a strike.

In times of low flow, the fish will be holding in the deeper pools unless they are spawning. Spawning fish can be easily located on the gravel beds, and you will typically see one female and several males. After a run, look for fish in the pocket

waters and the deeper runs. Generally, bright colored flies and lures work best in low light conditions and when the light is bright, use more subdued colors.

Fly fishing techniques are usually quite similar. Few salmon or steelhead are taken with dry flies, especially as the water gets colder. Normally some weight is needed to get the fly down. Either a weighted fly or split shot is used. Many fly fishermen

also use a float or strike indicator.

Although chinook salmon are not feeding when they are in the rivers, they will strike at bait or a fly. Often these fish will strike out of instinct or anger or to protect the redd. Putting the bait near the fish is essential. Like steelhead, you

can sight fish for chinook - and polarized glasses are very helpful for this. A chinook can bite lightly. If the line stops, lift the rod tip. If one is on, generally you will know it - it is pretty hard to miss it when you have a 25 pound fish

on the end of your line.

It remains illegal to take any fish by snagging. If it is not hooked in the mouth, you must release it unharmed. If the fish bolts away wildly, or if it just will not come in, you probably foul hooked it. A fish hooked in the side will bolt away due

to the pain of being hooked there. A fish hooked in the fin or the tail will be extremely difficult to bring in. Generally you can tell when the fish is fair hooked - it comes in head first and you can "lead" it towards you.

There is considerable controversy over the "lifting" of salmon. Lifting generally refers to drifting the hook into the mouth of the fish (which is opening and closing its mouth to breath), then "lifting" the line to hook the fish.

Some consider this unsportsmanlike; others consider this a fair way to catch a fish, particularly if they will not strike readily. It appears to be illegal "snatching" under current DEC regulations.

If you hook-up a chinook salmon, do not try to just muscle it right in. As some say, for the first few minutes the best you can do it hang on. Like any big fish, you must let it run and work it toward you as it tires. With these fish, it is more essential

to land them like an off-shore fish - raise the rod, then reel like crazy while you let the rod down, and repeat. If the fish runs, let it go; you will not stop it. If you want to land a big chinook, you may have to chase it. If it gets into the

riffles and heads for the lake, you will not pull it back through the fast water. Be prepared to walk (hopefully without falling) downstream after the fish. If you do so, be very careful of your footing and alert other anglers you are coming down.

Unlike chinook, steelhead are often feeding when they are in the streams unless they are spawning. They too can strike lightly and quickly and may spit the hook if you do not set it right away. However, if you hook up an eight pound fish, you will

certainly know it. Although the steelhead are not as large as the chinook, they are still in a different league than traditional inland trout. Many novice anglers lose many fish they hook. The two most common reasons the fish are lost are (1)

the drag is set too tight or does not work smoothly, and (2) the angler tries to "muscle in" the fish. In either case, the fish is lost either because the hook is pulled out of the fish's mouth or the line breaks. The drag should

be set just tight enough to be sure you can set the hook. Once the fish is on, you can always tighten the drag. If the drag is too tight to start with, you will probably lose the fish. Use your drag, let the bend of the rod work for you, and play

the fish until it tires and you can work the fish toward you. A steelhead will be difficult to land until it is ready, no matter what you want to do.

Additional Resources

Special thanks to Fran Verdoliva, New York DEC Salmon River Project Coordinator, for his assistance with this description.